The power of the media in shaping perceptions and influencing public opinion is well-known. The media have transcended time and age, going through various tools and forms, and stayed true to its influencing power.

The fourth estate, housing mainly traditional media, has opened a path for what is now known as the fifth estate, a home for non-mainstream and sometimes unconventional media forms and expressions. Without a doubt, this has had a considerable effect on public opinion, with freedom of expression and easier dissemination of otherwise ‘unpopular’ information as a benchmark.

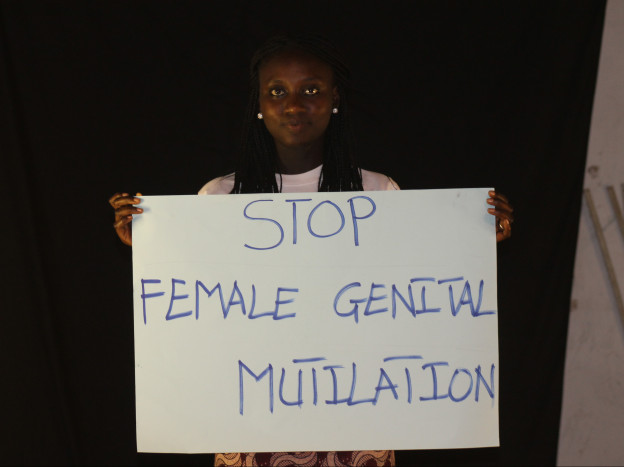

As with the famous egg and hen debate, we have witnessed similar discussions attempting to determine if the media influences social norms and practices, or whether the opposite would be more accurate. I believe it goes both ways, and this belief was solidified when I did my research for my undergraduate dissertation on the representation of women in the media. However, with increasing mutations in the way we communicate, I would think the media has a greater influence on our daily living and, as such, is one of the most powerful tools in advocacy on various social issues.

FGM Banned in The Gambia

On November 24th, 2015, The Gambia woke up to news of an Executive pronouncement banning the practice of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) in the country, with immediate effect. The announcement was met with various reactions, but what stood out most were the celebrations from the many activists, groups and organisations that have worked tirelessly for over three decades, calling for an end to the practice in The Gambia. The pronouncement was not an end in itself, but it was a huge means to this end that many have fought for, and can continue to work towards with even more hope for success.

Naturally, these celebrations came with several questions on how much the pronouncement will change, in the absence of specific legislation banning the practice and stipulating the penalties on those who refuse to adhere to this law. This was obviously a sure way of ensuring a permanent legal provision, creating more opportunities for activists and rights advocates to carry out their work. Barely a month later, the National Assembly of The Gambia enacted a bill to this effect, making The Gambia one of eighteen African countries banning the practice of FGM.

The legislation on FGM does not only give renewed hope to end the practice in The Gambia. It comes against a backdrop of great controversy, given the sensitive nature of FGM, and the cultural and religious links that have been used as grounds for its perpetuation. Activists and advocates have received much backlash and opposition – sometimes violent – from individuals and communities that support the practice and guard it jealously. Some have been “persecuted and prosecuted” for their stance against the practice, and for openly denouncing it for its harmful effects on girls and women. For many of these people, this is enough reason to celebrate a public display of political will to end the practice. The opportunities are many, and the channels for advocacy to end FGM have increased, especially on mainstream media. This has not always been the case.

The case of the media

In May 1997, a new GAMTEL policy on media treatment of the issue of female genital mutilation advanced that “the broadcast by Radio Gambia (RG) or Gambia Television (GTV) of any programmes which either seemingly oppose female genital mutilation or tend to portray medical hazard about the practice is forbidden, with immediate effect. So also are news items written from the point of view of combating the practice.” The policy went on to direct that “GTV and RG broadcasts should always be in support of FGM and no other programmes against the practice should be broadcast.”

This policy meant that efforts at the grassroots level, by organisations like the pioneering GAMCOTRAP, would be limited to the communities and not disseminated to a wider audience, possibly leading to more impact. What would have been a channel for easier access to the Gambian people then risked becoming a platform to counter the efforts of these groups in the communities, opening more girls to the possibility of being cut. The negative impact on the campaign at the time is evident, while highlighting a restriction on the media’s role of not just entertaining, but informing and educating the people.

In the years that followed, work to influence the abandonment of FGM in The Gambia continued, and this included training of media personnel to increase coverage on the harmful effects of the practice and the work of civil society organisations in that regard. Notably, there was still a huge gap in coverage which, when filled, would have contributed greatly to the campaign.

Additionally, the nation has been witness to pronouncements by a religious leader, calling for a ban on activism against FGM in The Gambia. The same individual has made regular appearances on the media, extolling the benefits of FGM and advancing the idea that it is a religious obligation. The effects of his statements will be left to your conclusion, given the perceived religious nature of Gambian people and daily living.

In recent years, however, there has been a significant change, perhaps attributable to the increased intensity of the campaign, especially featuring youth voices that were hitherto least prominent in the movement. The use of social media to engage in conversation and share messages on FGM should not be overlooked. There has also been a notable increase in media coverage of FGM since the First National Youth Forum on FGM in The Gambia in 2014, jointly organised by Think Young Women and Safe Hands for Girls in partnership with organisations like GAMCOTRAP, TOSTAN, Wassu Gambia Kafo and other remarkable actors in the field. Stories on related events made it to national TV, but it important to note that these were often broadcast under the umbrella of Gender-Based Violence, often shying away from the specific issue of FGM.

On more than two occasions, as part of a cultural show on the channel, female circumcision was featured as a rite of passage, with images of celebrations in selected communities. Upon examination, this was a statement of support, even if very subtle, and did not do well to complement the work being done to end the practice. Featuring the celebrations as a cultural activity to be valued might have contributed to convincing viewers, even further, that FGM is a culture that should be appreciated and perpetuated, despite the information on its harmful effects on girls and women. There was still so much more work to be done, and little time to do it all.

Welcoming a New Dawn

As expected, following the Executive pronouncement and the consequent enactment of specific legislation against FGM, there has been a flood of stories on both print and audio-visual media in The Gambia and abroad. This is a significant turn, and a commendable one, especially since efforts are now being shifted to intensify sensitisation , including on the new legislation. The change on the local front will go a long way in raising more awareness and hopefully influencing a voluntary abandonment of the practice, which may be more effective and permanent than abandonment resulting from the new deterrent. The local media is indeed catching up to this new wave.

On the night of January 16th, GRTS aired one of its most interesting shows, “The Forum”, which features conversations on social issues, guided by professionals and experts on the subject. It was a pleasant surprise to learn that the night’s discussion would focus on FGM, and would feature opinions from professional health personnel, including one of the most renowned gynaecologists in The Gambia, at present. It promised to be an interesting discussion, further enriched by the phone-in feature that gave viewers the chance to call and share their thoughts on the topic. The expectations were met, and the discussions looked deeply at the effects of FGM especially on the physical, psychological and psychosocial wellbeing of girls.

When the phone lines opened, a few viewers called in to express appreciation for the program, as it had given them a new understanding of the dangers of FGM. One lady remarked that it may be too late for those who’d already undergone the practice, but there is still a big opportunity to protect the girls who are currently at risk. Judging from the calls that followed, this was not an isolated belief and the protection of those girls is a possibility to be explored, with the new legislation as solid backing.

The admission reminded me of the reactions of participants at the aforementioned youth forum, when they were exposed to images showing the health effects of FGM on girls for the first time. Outlooks were changed and resolves were strengthened, fuelled by a new understanding of its gravity. This, in essence, represented the power of the media in changing perceptions.

Conclusion

While the next few years will test the effectiveness of these new provisions and the commendable change, there is reason to remain hopeful for an FGM-free generation. It takes off from the decisions made today and the manner in which work is done to this effect, bringing together all actors and stakeholders from government and civil society to ensure targets are met and girls are protected from harm.

Addressing the issue of FGM also means examining support mechanisms for the girls and women who now live with the complications of the practice. A lot of attention is focused on prevention, but it is also important to look into care and restorative measures to facilitate the regaining of dignity and the maintenance of good health.

The more awareness raised among the people, the greater the chances of eliminating this practice and ensuring women fully enjoy their human rights, especially to life, dignity, sexual and reproductive health among others.

The media is the major gateway to raising this awareness and awakening people to the realities of Female Genital Mutilation and its effects on the health and wellbeing of women and girls. This new turn will go a long way to complement sensitisation efforts in communities, and contribute to more success in the campaign to end FGM in The Gambia.

As highlighted, the ban on the practice in The Gambia has opened up new opportunities, and that is worthy of a moment of celebration, as the relevant actors take the next steps to realising concrete change.